Entity Framework Basics

We recently had an incident in production at my place of employment where memory spikes were intermittently occuring in one of our .NET web applications. The problem was eventually tracked back to some Entity Framework code that had been written by a senior level developer. At first, I was shocked that this developer didn’t understand the code he had written and why the code was problematic. However, certain abstractions within the Entity Framework make this particular issue very easy to overlook without a solid understanding of the library.

What this post isn’t about

This post is not about showing you how to use Entity Framework or how to do “code first”. This post is intended to help you understand what exactly is going on behind the scenes, and how to prevent the situation described in the previous paragraph. Most of the Entity Framework tutorials I’ve read mention nothing about the “magic” occuring as you write your fancy chained linq statements to pull data out of a database. This is information you must know if you are looking to solve problems with EF.

Materializing

When considering the performance of your application, materializing has to be your #1 concern when using EF. So what is materializing? I don’t really know the official meaning of matrializing, but I think of it as transfering data into in-memory objects. That concept is extremely important when using EF, and here is why.

Let’s say we have the following service to get some data from our database:

public class ProductService : IProductService

{

private IRepository<Product> _repository;

public ProductService(IRepository<Product> repository)

{

_repository = repository;

}

public IEnumerable<Product> GetAllProducts()

{

// assume the GetAll method returns an IQueryable

return _repository.GetAll().ToList();

}

}And then we have the following action method to display that data in a view:

public class ProductsController : Controller

{

private IProductService _productService;

public ProductsController(IProductService productService)

{

_productService = productService;

}

public ActionResult ShowProducts()

{

var sortedProducts = _productService.GetAllProducts().OrderBy(x => x.OrderDate);

return View(sortedProducts);

}

}This is bad! If you know why this is bad, you can leave now - this post isn’t meant for you. If you do not know why this is bad, stop writing Entity Framework code immediately and don’t do any more until you fully understand the contents of this blog post.

IQueryable

When you write an Entity Framework query, you are more than likely using common LINQ statements to fetch your data. For example:

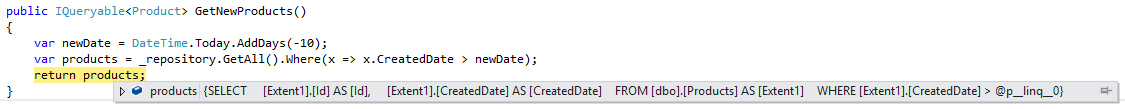

public IQueryable<Product> GetNewProducts()

{

var newDate = DateTime.Today.AddDays(-10);

var products = _repository.GetAll().Where(x => x.CreatedDate > newDate);

return products;

}If we debug this code and take a look at what’s going on with that products collection, we see this:

As you can see, our products haven’t been queried yet. That LINQ statement is doing some magic to build a SQL

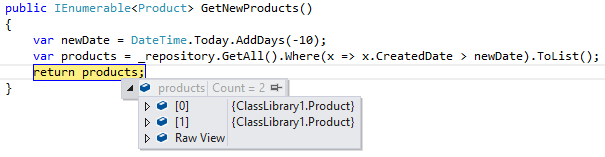

query. Now look at what happens if I add a .ToList() to the end of that LINQ statement:

The SQL transaction has now been executed and your list is in memory. For the sake of this demonsration, my product list is very small. However, a real-world production database could have millions or even billions of products with a strategically placed index on the CreatedDate property. You do not want your web server sorting and querying this data in memory. You want SQL server to do the work.

So I should never use .ToList() right?

Wrong. I would recommend using a .ToList() explicitly at some point to denote that you are now converting your

query into an in-memory list. Even better, wrap the .ToList() method into an extension called something like .Materialize().

If your IQueryable ends up making it to the view, the view could end up doing all sorts of interesting things to materialize data.

When writing EF code, please be mindful of what is going on behind the scenes. Understand and write self-documenting code to explain exactly

where the query is executing. Doing this will prevent strange memory spikes from bogging down your software.